Entry No. 13 Bridgerton Necklines & the Green Heart Gown

I wasn’t able to get as many photos of this gown because I took an 8 minute video of first part of this presentation.

Why, Hello Darling!

I’ve just come from a curator chat at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, and I took far too many photos not to share with you.

The talk was led by Ned Lazaro, assistant curator at the Wadsworth—a beautiful space that owes much of its history to J.P. Morgan. In 1907, Morgan pledged $500,000 for what became the Morgan Memorial addition, and his generosity—and that of his family—helped shape the museum we see today. Hartford City Hall, another architectural jewel just steps away, was also built during a period when the city benefited greatly from the philanthropic spirit of its wealthiest citizens. Together, these buildings stand as proud symbols of Hartford’s artistic and civic legacy, with their gleaming marble halls and stately presence.

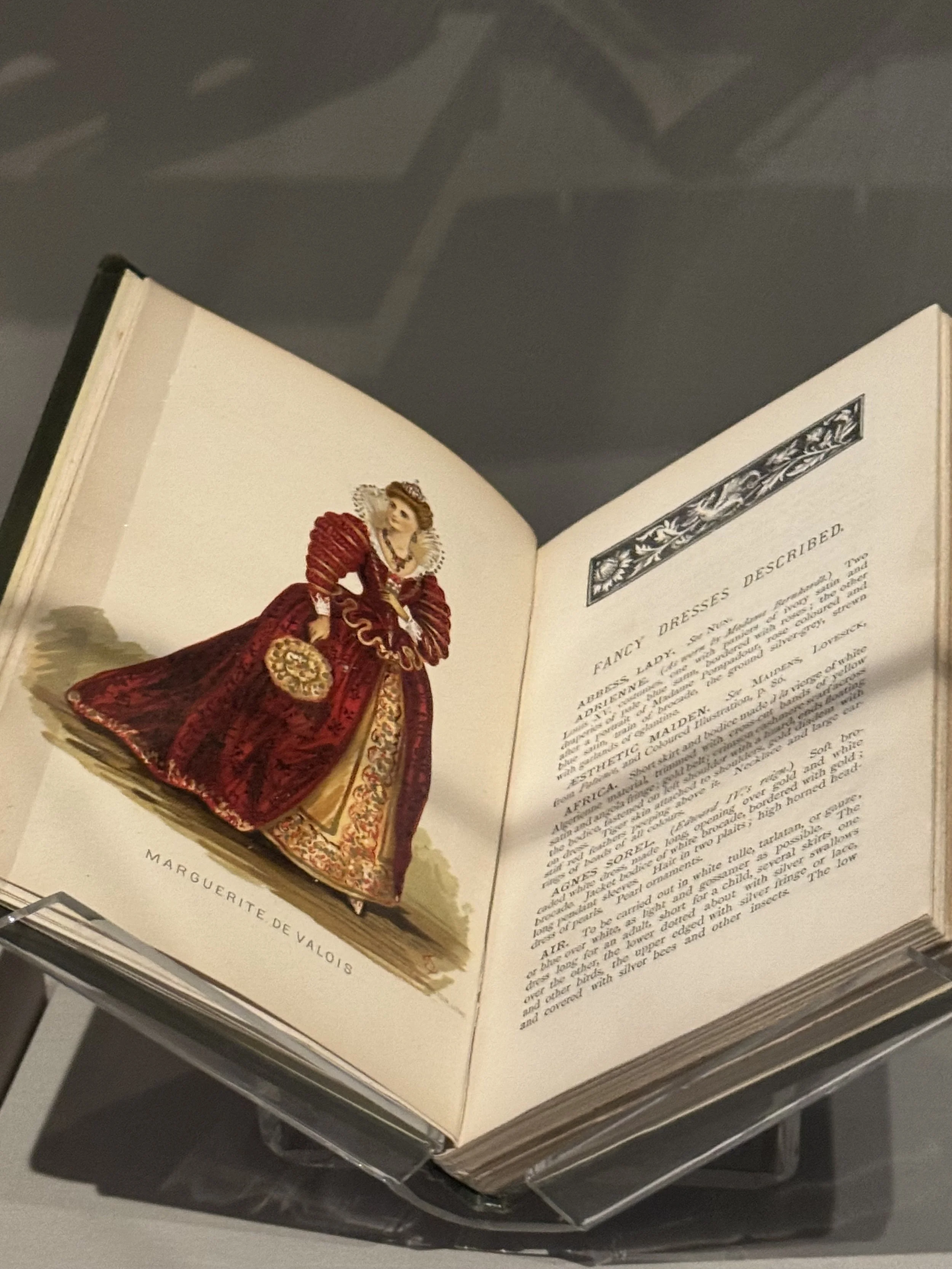

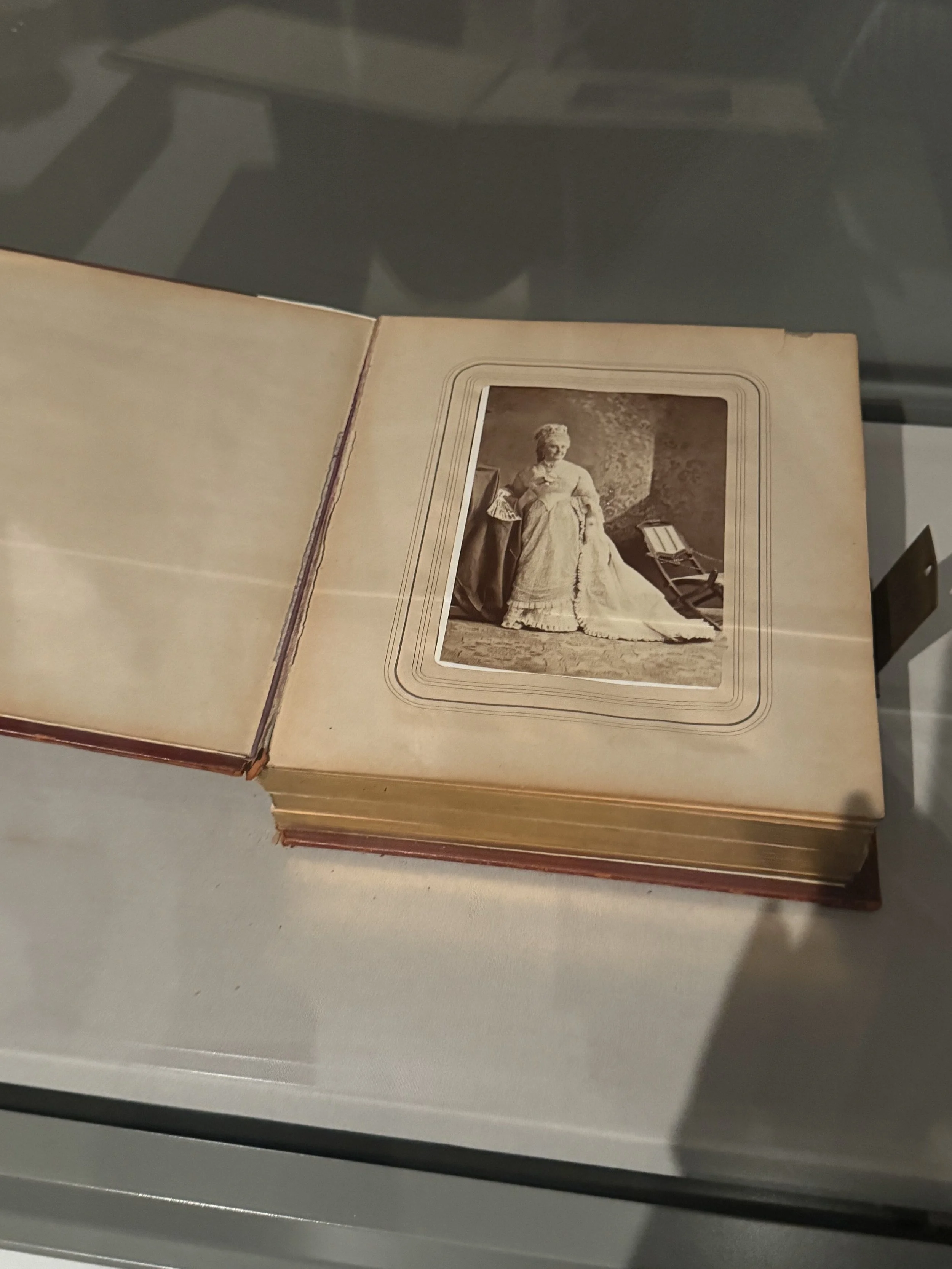

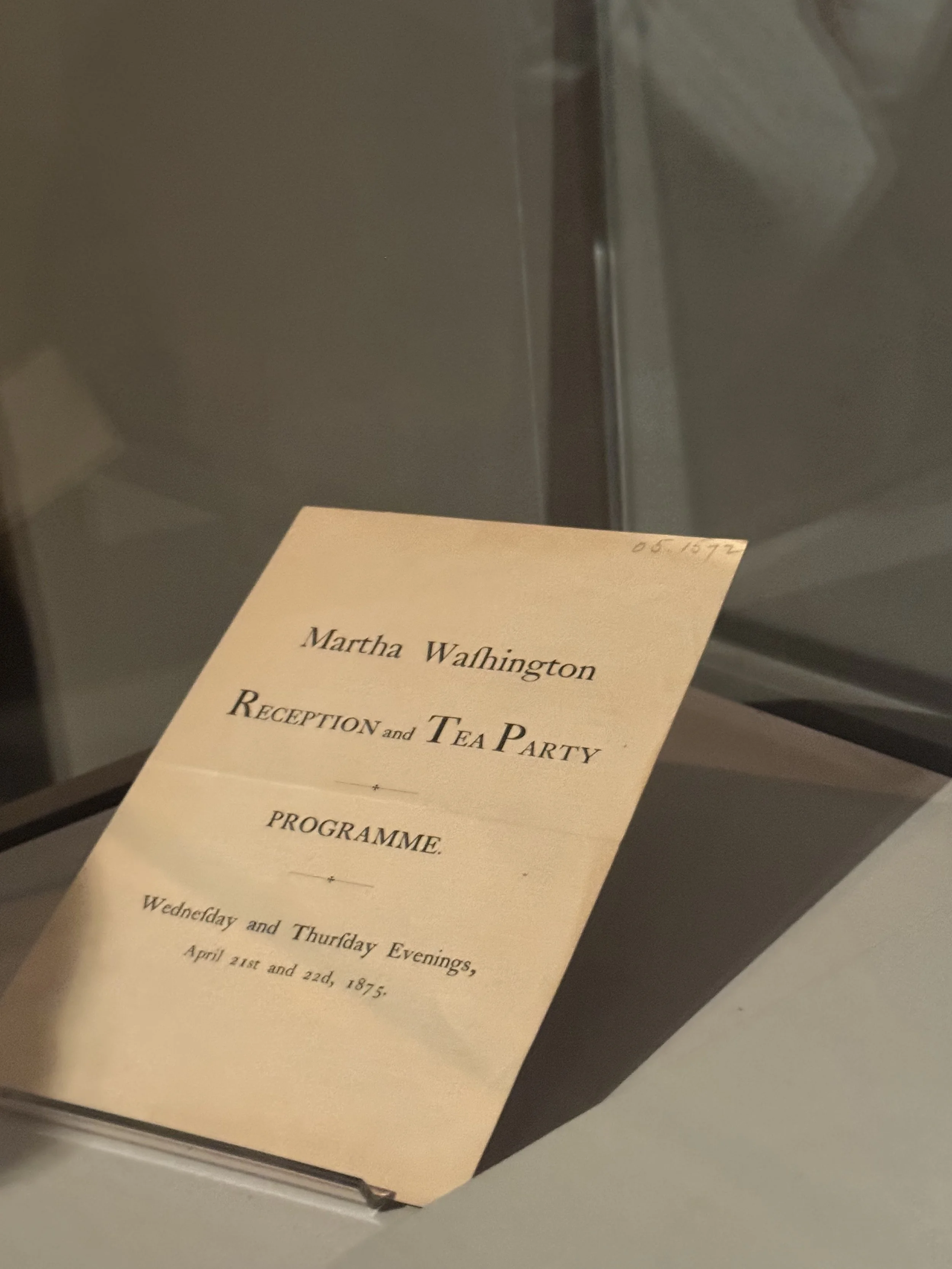

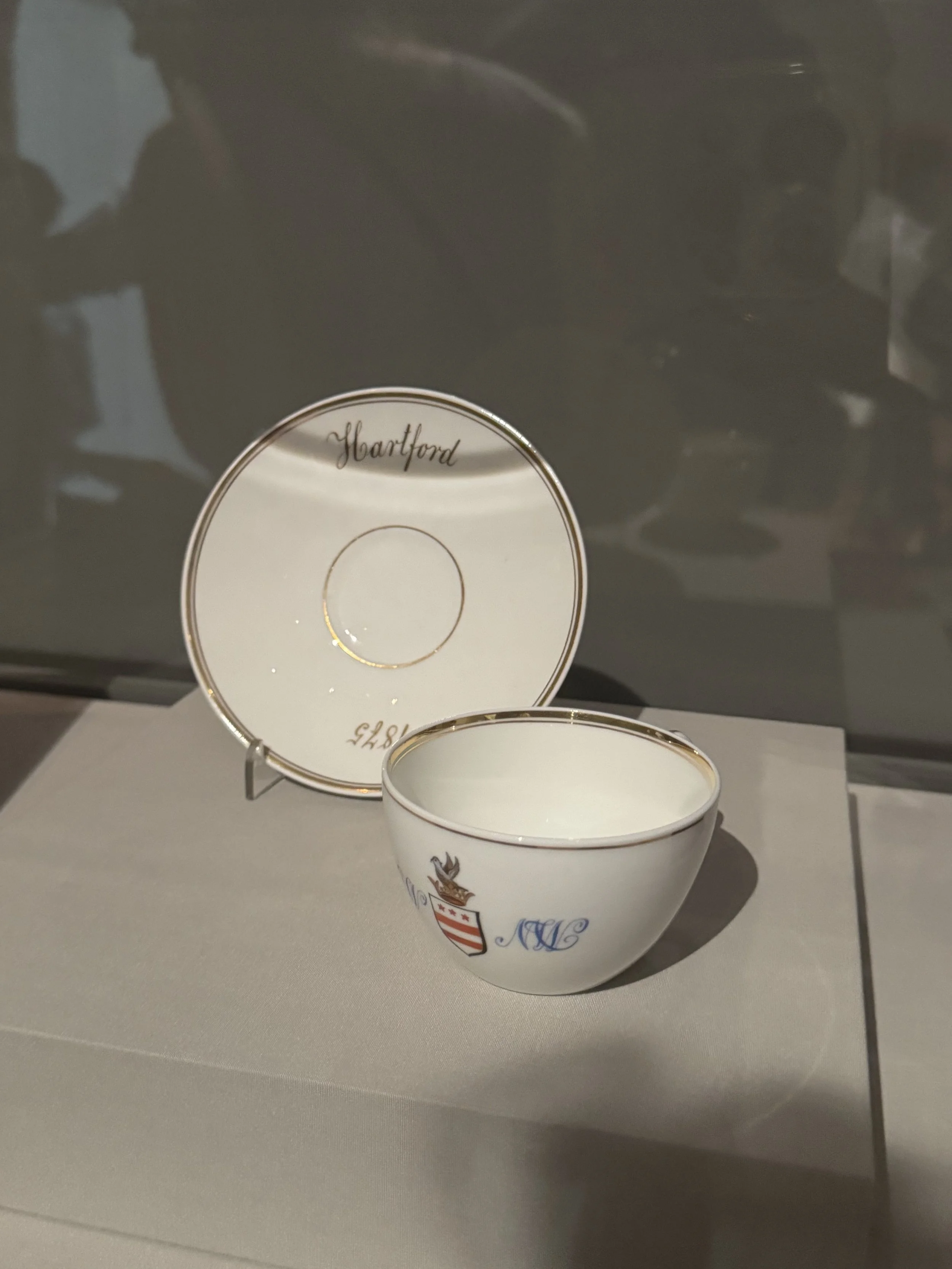

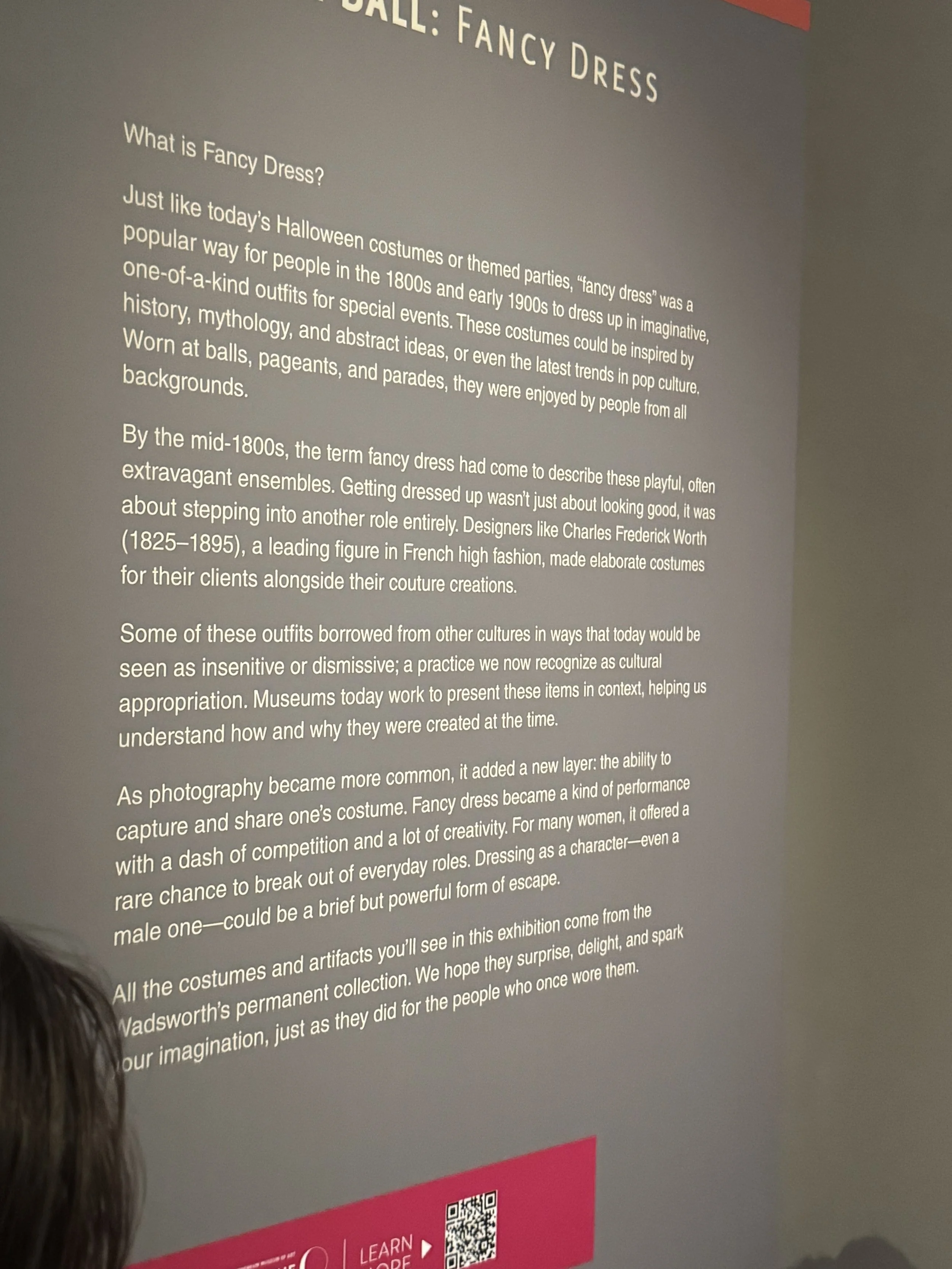

This was actually my second curator chat (I haven’t shared the first one yet—but don’t worry, those photos are coming soon). Today’s was called Fancy Dress. Now, if you’re picturing what we call “fancy dress” today—something you’d wear to a prom or gala—you’d be a little off. In the early 1900s, "fancy dress" referred to elaborate costumes. Not Halloween costumes, but the extravagant ensembles worn for elaborate costume balls and themed society events. People of means would “dress up” as figures from history, foreign lands, or entire past eras—an evening’s permission slip to play another role entirely.

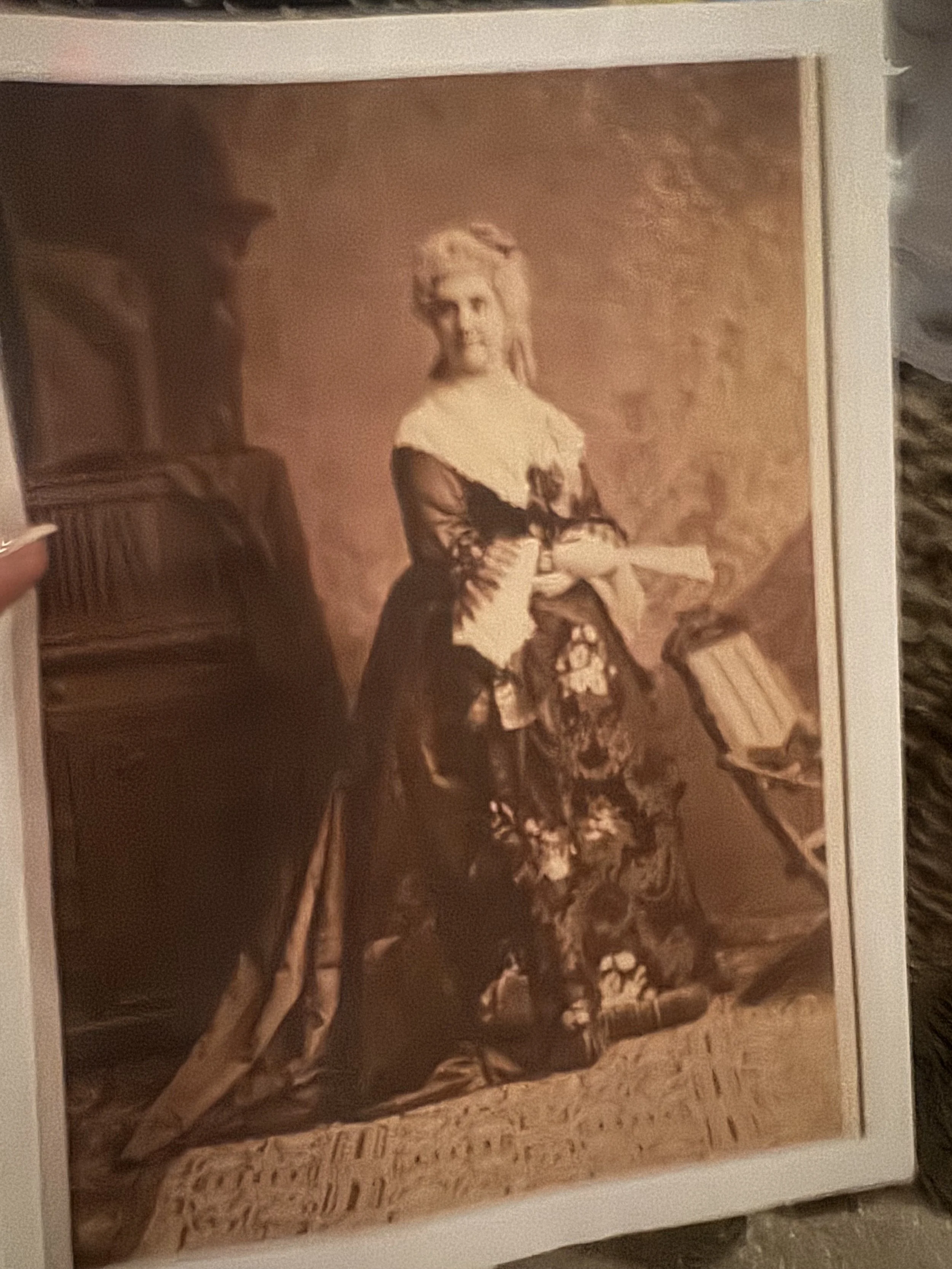

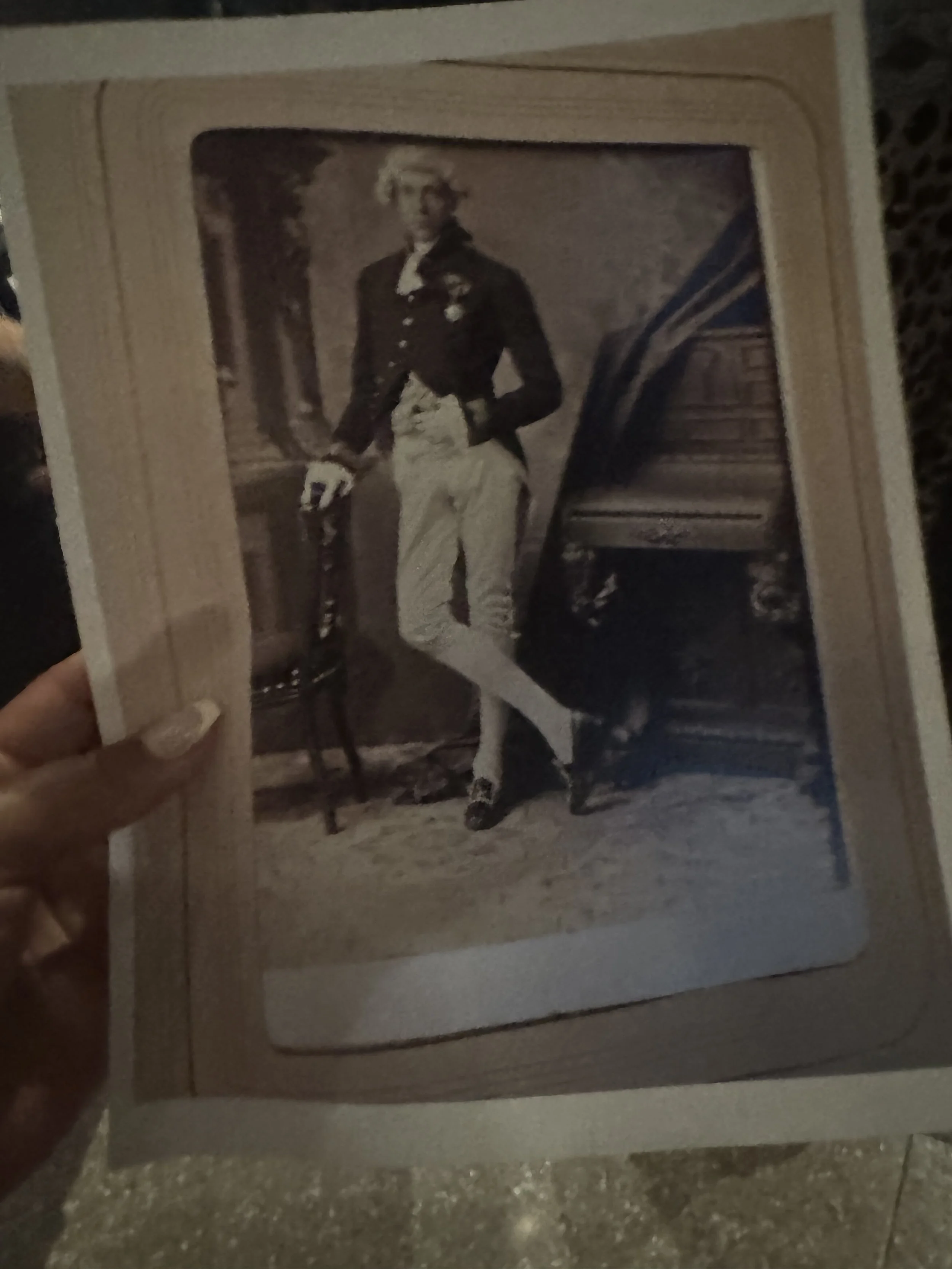

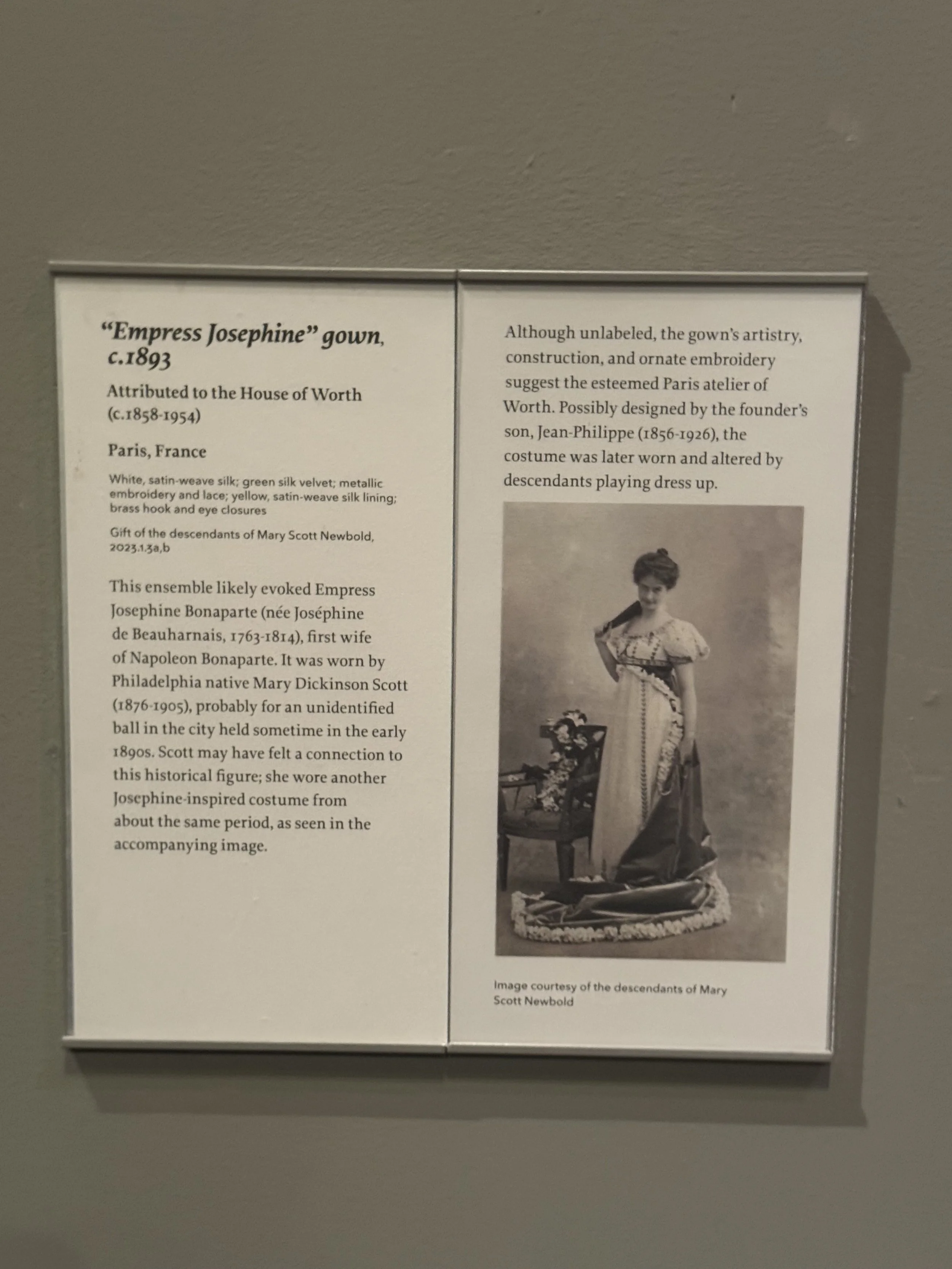

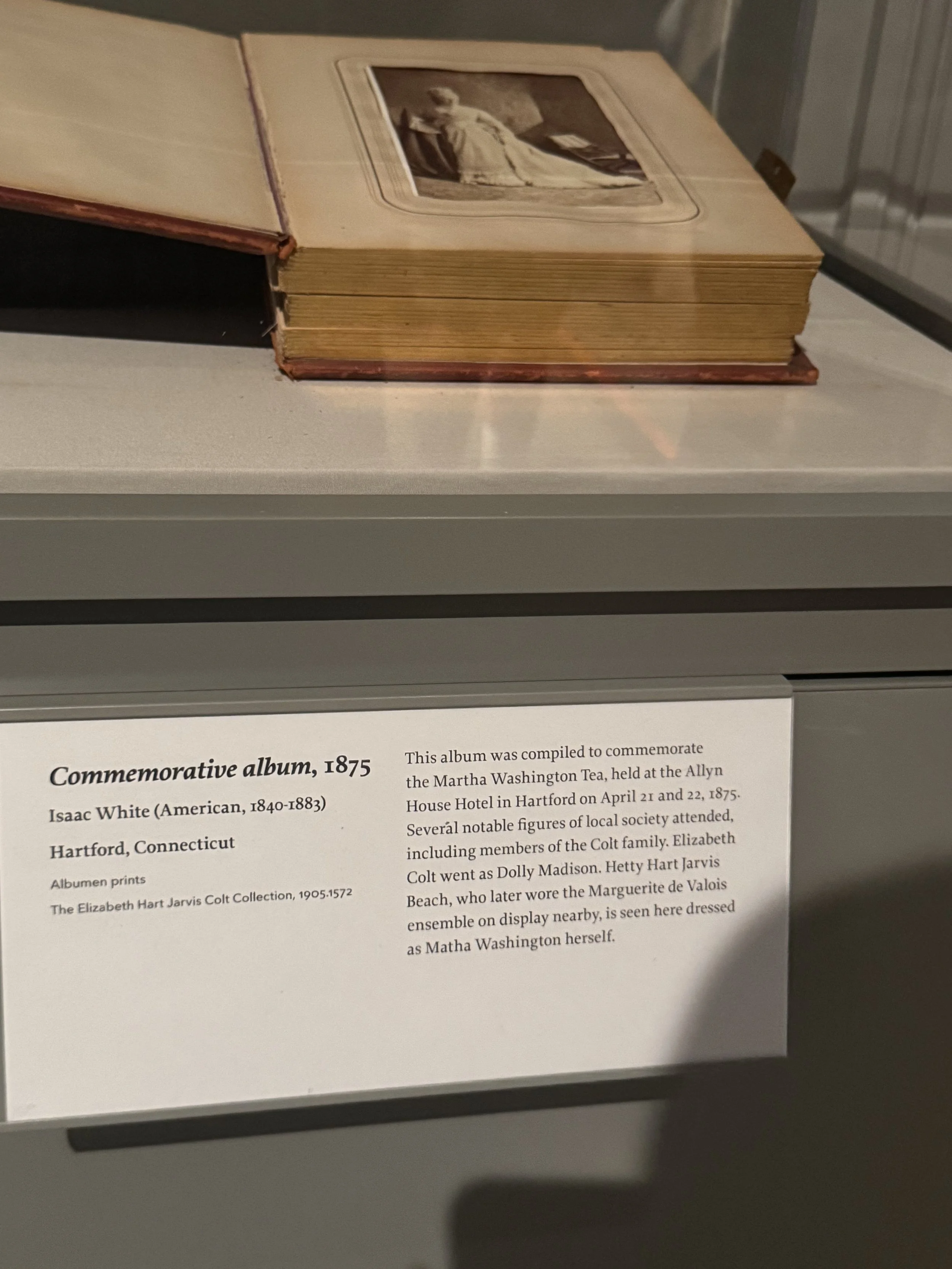

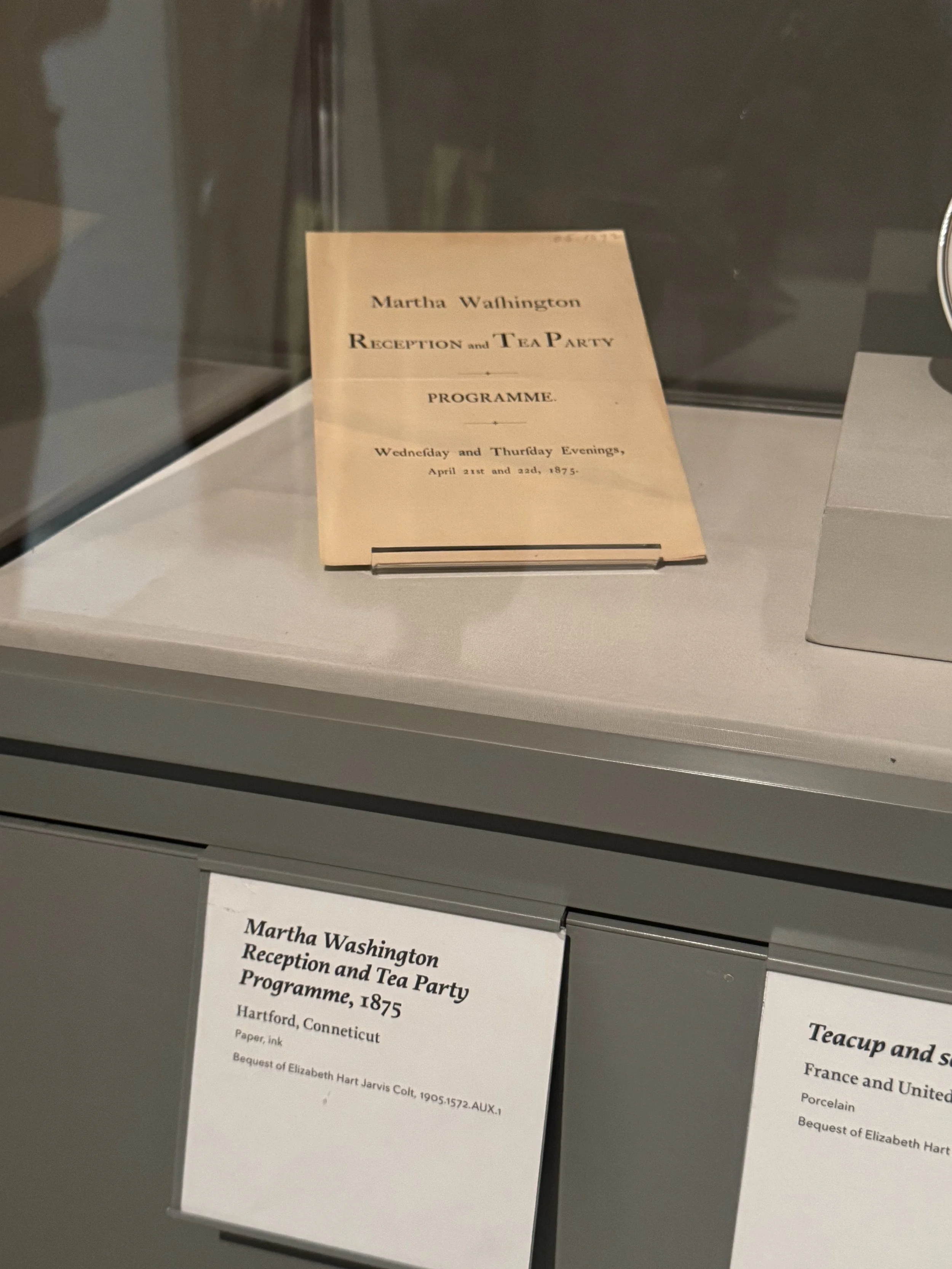

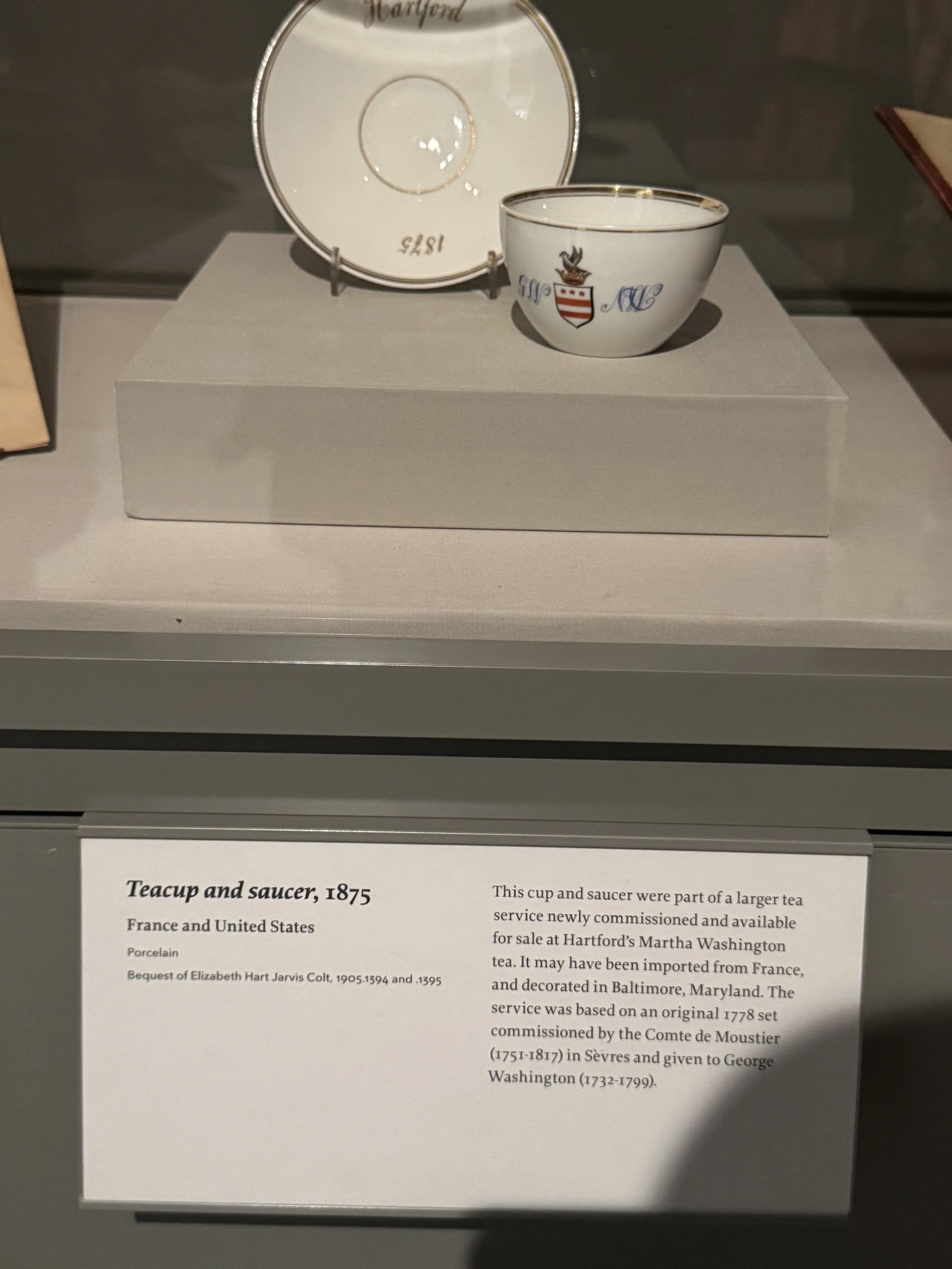

Ned walked us through the garments on display—mostly women’s gowns with a few pieces for men—and the events they once graced. One was a grand party at the Wadsworth on April 20, 1927; another, a Martha Washington Tea, which featured a gown nicknamed Josephine (you’ll see her in my photos).

The very first gown we encountered was known as the Green Heart Gown. Picture a bodice crowned with a large velvet heart in deep green, puffed sleeves, and a slender A-line skirt dotted at the hem with smaller velvet hearts. I loved the sleeves on this one.

But my personal favorite was the Josephine dress—woven satin silk in an unusual, almost acidic green-gold hue. Ned noted the fabric’s synthetic dye, evident in how it’s aged. It made me want to dig deeper into the difference between how natural versus synthetic dyes wear on silk—especially since this gown’s color remains so bold.

Nearby were two costumes with a Turkish influence, hinting at the sense of play and departure from one’s usual station that fancy dress allowed. Ned noted, however, that this inspiration was not without its complications. A placard in the exhibit referenced the cultural appropriation embedded in these costumes—how garments were often romanticized, misunderstood, or stripped of context by the high society wearers of the time. It was a thoughtful reminder that while these ensembles are beautiful to the eye, they also carry a difficult history worth acknowledging.

But the pièce de résistance was indeed Josephine. Said to weigh about 10 pounds, much of that from its elaborate embroidery and tiny pieces of metal worked into the design, it’s the kind of dress that reveals more the longer you look. Beneath ruffles and a heavy velvet shawl, I spotted a multicolored watercolor insert—tucked away like a secret.

It’s my favorite in the exhibit, and with a few adjustments, I think a modern bride might love it too. It had that unmistakable Bridgerton-era romanticism, but far more flattering than many gowns of that period, which tend to hide the figure. This one skimmed the hips beautifully. Its low neckline, however, brought to mind the 18th-century fashion for daringly deep décolletage—so low, in fact, that exposed nipples were not only possible but often expected in elite circles. Some women even enhanced the look with rouge. If I were recreating it for a contemporary bride, I’d raise the neckline just enough to avoid any accidental history lessons.

The gown’s puffed sleeves, lace-up back with a bow, fringed hem, and lavish embroidery on both dress and velvet scarf made it every inch the high-society showpiece.

Someone asked Ned about prices, and he explained that cost depended on whether the garment was couture, purchased as a stock piece, or custom-made. In the 1920s, prices ranged from a few hundred dollars to several thousand—meaning tens of thousands in today’s money. I’ve read that in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, some gowns cost as much as a townhouse, serving as visible proof of social standing and a tool for securing a “suitable” marriage. Looking at Josephine, I can believe it.

Two other gowns rounded out the room. One, from the 18th century, was modest, with a scarf at the neckline—reminding me of the clothing I wore when portraying Fanny Freeman on the Farmington Freedom Trail (1840s). The other was an explosion of detail: bows, appliqués, beading, embroidery, lace-trimmed collar and cuffs, and bishop sleeves split open in the style of kings past.

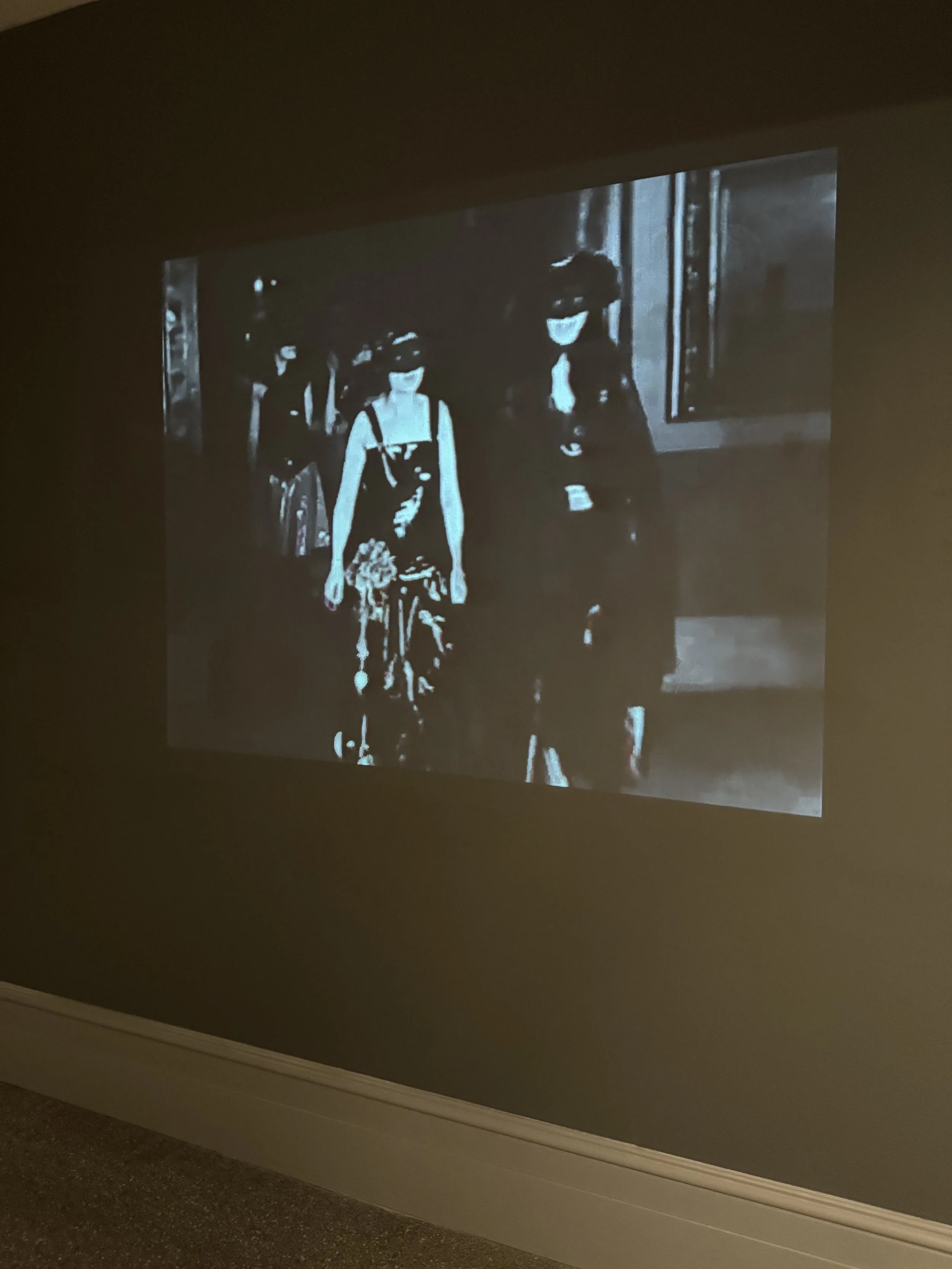

The exhibit runs until October 5th, and I highly recommend it. There’s even a vintage video showing the arrival of guests—some in groups, some alone, one atop a fake hippopotamus. (Yes, really.) Hard to believe these scenes are over a century old. I took a few short videos during the curator chat as well—those will be appearing on my Pinterest account if you’d like to hear the behind-the-scenes murmurs.

At the end, I spoke briefly with Ned and shared that I own a vintage wedding ensemble from 1897, a gift from my mother-in-law. There was even a small slip of paper inside with the year written on it. But knowing how clothing was treasured and passed down, it could be older still—possibly 150 years or more. It’s beautifully made and remarkably preserved, a tangible thread connecting me to the kind of craftsmanship that filled the Wadsworth’s marble halls that day.

If you do visit the Fancy Dress exhibit, let me know what you think. And if you’re not in Hartford, does your local museum host events like this? If you don’t know, it’s worth finding out—they can be unexpectedly rich sources of inspiration.

With Love,

Dani